Where Do We Go From Here? The Story of Syria's Public Health System

By Cierra Carafice

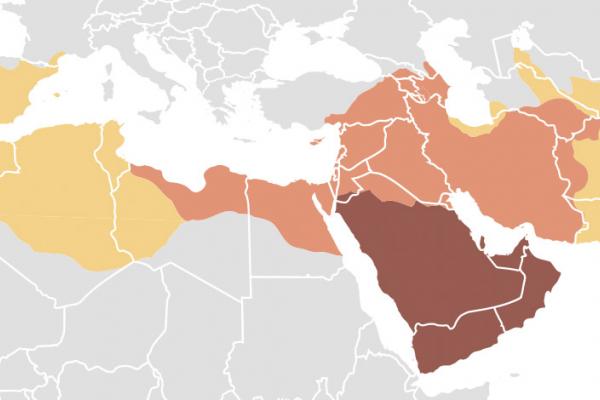

The ongoing civil war in Syria has been a very visible and heavily discussed conflict. However, one of the more obscure facets of this war is the toll it has taken on Syria’s public health system. While people may know about the growing refugee crisis and the trauma faced by individuals caught in the crossfire, including women and children, the overall collapse of the entire Syrian public health system is not often debated due to its complex and unglamorous nature. Nevertheless, the issue is of growing importance. A country cannot be rebuilt if its inhabitants are sick and dying of treatable diseases, injuries, or malnutrition. Also, in today’s increasingly mobile world, any epidemic is a potential threat to everybody and conflict-zones are the perfect breeding grounds for disease. In light of this, it is important for the global community to understand why the Syrian health system failed and what can be done in the future to fix it.

One of the biggest losses in the war is that Syria’s healthcare system, which once was boasted of as the best in the Middle East1, is now in shambles. Before the conflict began, Syria had made major improvements to its public health systems. The average life expectancy at birth had risen from 56 years in 1970 to 75.7 years in 2012.2 The infant mortality rates were continuously falling and the under-five mortality rate had reached record lows. In addition, the Syrian Arab Republic was in the middle of an epidemiological transition from communicable to non-communicable diseases.3 Unfortunately, this progress was all reversed when the civil war began.

While a side-effect of war is typically declining public health, Syria’s healthcare system has seen devastating damage in comparison to many modern-day conflict zones. So, what lead to the annihilation of the Syrian public health systems? It seems to be that military forces, both Syrian and Russian, are targeting and destroying hospitals, health workers, and medical supplies in direct violation of the Geneva Convention, the laws that govern war, which condemns attacks on civilians through the destruction of water supplies, food, and hospitals.4 This has rendered health facilities almost completely non-functional. Many of the health care workers who remain in Syria are faced with daily threats to their lives and they are forced to work in make-shift hospitals with almost no supplies to treat their patients. Medical supplies are severely limited, despite UN humanitarian efforts, because the ground forces are preventing the convoys from reaching the 12.8 million people that require medical assistance.4 Additionally, the Syrian air force is becoming known for their “double-tap” strategy of attacking their targets a second time after the first-responders have arrived.4

Gallery Image Link:

Since 2012, the average life expectancy at birth has fallen 20 years, putting the average lifespan back to those which would have been seen in 1970. The overall quality of life has also declined for the Syrian people. The large-scale displacement of the Syrian population has created unsanitary conditions, like contaminated water supplies.2 The country faces a lack of shelter, energy sources, and sanitation services paired with overcrowding and food insecurity.3 These conditions have fueled a resurgence of diseases like polio, cholera, typhoid, hepatitis, and parasitic infections, reversing the epidemiological transition that was happening in 2012.2 And the Syrian people are not just subjected to the rise in communicable-diseases. They are also facing a huge mental health epidemic, as the trauma of war and the stress of everyday living in a conflict zone takes its toll on the population.2

Facing this bleak situation, it is hard to know where to go from here. As the war continues, it seems unlikely that the country will find stability anytime soon. With this in mind, it may seem pointless to shift the focus to rebuilding the public health system. However, now is the time to look beyond crisis response and start forming long-term strategies of planning and recovery.1 Syria is facing a severe shortage of medical professionals and a huge amount of individuals in need of medical care. The healthcare system is understaffed and a generation of Syrian children have been deprived of schooling and will not be able to fulfill the need for health workers.4 Rebuilding the system will require replacing at least 1,000 doctors, nurses, and other health professionals who have disappeared, fled, or been killed.5 There will also need to be a mass construction of hospitals, training centers, and universities in order to provide the structural foundation necessary for a functioning health system.5

Gallery Image Link:

By Scott Bobb - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gugN3SNBQJQ&feature=plcp, Public Domain

Although this seems like a daunting task, organizations and individuals are already taking steps to alleviate the strain on the healthcare system and work towards rebuilding it in the future. A major contributor to these efforts is the World Health Organization (WHO). According to their last Syrian Arab Republic Donor Update, the WHO has been circulating vaccinations, working to alleviate mental health issues, and training health workers on various interventions through online training programs.6 Specifically, the WHO have launched two major vaccination campaigns against Measles and Polio. They have also created community centers in the north of Syria in Al Hassakeh that provide mental health and psychosocial support services. In addition to this, the WHO has created two major programs called the Self-Help Plus (SH+) campaign and Psychological First Aid (PFA) in order to alleviate some of the mental strain on Syrian people. The SH+ campaign uses stress-management materials in order to teach individual how to cope with extreme environmental stress and as part of the PFA, the WHO trained health care providers in stress management and self-care strategies to help themselves and others who have experienced distressing events during the war.6 As for replenishing the health care workforce, the WHO is training workers across Syria with online courses and by connecting doctors in Turkey to Syrian health workers using Skype.6

In addition to the steps taken by large, international organizations like the WHO, local Syrian healthcare workers have taken their own steps towards alleviating the healthcare crisis in their country. In January of 2017, the newly established Sahel hospital began operating and treating those in need free-of-charge.7 This hospital, built under the supervision of the Free Latakia health department and the Free Syrian Army, is fully equipped to treat emergency cases and it has the space for surgical and in-patient wards.7 Equipped by Medecins Sans Frontieres, this hospital aims to fill a serious lack of health care in the Latakia area.7 This hospital marks progress in offering medical services in opposition-controlled areas and it shows how important local initiatives can be.

The United States is not left out among international countries providing aid to Syria’s healthcare system. Due to the diverse population in the U.S., many individuals have invested interest in the Syrian public health crisis. A significant amount of the medical brain-drain from Syria has been to the United States. The emigration factor of Syrian physicians to the United States is around 13%.8 According to the American Medical Association, the total number of Syrian Physicians practicing in the United States as of 2008 was 3,900, about .4% of the workforce.8 Since the start of the Syrian crisis, the U.S. has provided more than $6.5 billion in humanitarian aid in support of the United Nations and NGOs operations to provide emergency relief to Syria and its neighbors.2 Additionally, the Syrian American Medical Society is actively facilitating a rotation of healthcare volunteers in Syria.2 Even Yale University has offered some assistance to the healthcare system in Syria. Because Syrian medical schools were destroyed and medical personnel are being targeted, students and faculty of Yale School of Public Health created a program to aid medical students in Syria so they can safely continue their education. The program accomplishes this by sending tablets with medical information, which can facilitate online instruction, in order to provide access to online courses and downloadable medical education materials to Syrian medical students.9

Dr. Marcel Yotebieng, a professor at The Ohio State University and an expert in global epidemiology, has done extensive work with public health systems in African countries like Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo which have faced issues similar to the situation in Syria today. He was able to apply his knowledge of these countries to the current health crisis in Syria in order to discuss what he believes will be necessary for Syria to recover in regards to its health system after the conflict has ended. Dr. Yotebieng emphasized that the most important aspect of the Syrian civil war is that there appears to be a clear winner. Assad, with the help of the Russian military, has brought a majority of the country under his control.10 Dr. Yotebieng said that the situation is comparable to Rwanda, where the Tutsi's gained control of the country after the war and were tasked with rebuilding a country with deep ethnic divisions that was ravaged by conflict and disease. Today, Rwanda has one of the lowest infant mortality rates in its income bracket and its health system has been recovered beyond expectations. Dr. Yotebieng believes that Syria will follow the same path because

"there is a clear winner of the war who now has the responsibility to provide for the remaining population and rebuild the country if they want to remain in power."

However, no country can begin reconstruction efforts if there is no money. Without a functioning economy there will be no improvement to the situation in Syria. While discussing the possible future of the health system in Syria, Dr. Yotebieng said that the rate of economic growth will determine how quickly Syria's health infrastructure recovers. However, if the economy recovers quickly and Syria is able to find money and resources, Dr. Yotebieng predicts that the health infrastructure will be one of the first things to be rebuilt. As for the shortage in medical professionals and health care workers, Dr. Yotebieng says he believes Syria will quickly be able to recover those resources. Although many of the doctors have fled or been killed, those who remained are highly dedicated to rebuilding their country and their livelihoods. While doctors and nurses who fled the country will most likely not return unless they are assured safety and the job or life prospects are significantly better than wherever they emigrated to, neighboring countries like Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan will step up to help provide personnel and medical training because they have an invested interest in containing the lasting effects of the war. As for the mass destruction of physical health infrastructure, Dr. Yotebieng said that these structures can be built from scratch to be more modern and efficient than the structures from before the civil war. Also, while a majority of Syria did face heavy destruction, there were parts of the country that were preserved. These areas can serve as a basis on which to model the countries health organizational system and infrastructure. Overall, Dr. Yotebieng believes that Syria's health system will make a quick and full recovery as long as there is a clear winner, the economy recovers quickly, and there is an organizational system put in place that is focused on improving Syria's health situation.

The next step is to look to the future. Although there are still areas of conflict and the country is not yet stable enough for reconstruction efforts to begin, it is time for the world to think about the major efforts that will be required to rebuild the Syrian public health and healthcare infrastructure. This rebuilding effort will, after all, require years of work by local and international communities.2 After the conflict, Syria will need a development process designed to examine and assess the health situation using a holistic approach. This process will need to be undertaken by international organizations in collaboration with the national government of Syria.3 In developing these processes, Syria and international organizations will need to look to other countries which have faced similar conflict situations and managed to rebuild or even advance their public health infrastructure. Syria will also need to focus its efforts on rebuilding its economy if it wishes to restore its once prosperous health system.

Sources:

- Sengupta, Seema. “Rebuilding Syria’s Decimated Medical Infrastructure.” Asia Times, 16 January 2017. Web. 11 September 2017.

- Phillips, Steven. “Syria’s Compounding Health Crisis.” The Washington Institute, n.d. Web. 12 September 2017.

- Kherallah, Mazen; Alahfez, Tayeb; Sahloul, Zaher; Eddin, Khaldoun Dia; Jamil, Ghyath. “Health Care in Syria Before and During the Crisis.” NCBI: US National Library of Medicine: National Health Institution, n.d. Web. 12 September 2017.

- Li, Gina. “Hospital Bombings Destroy Syria’s Health System.” Health and Human Rights Journal, 11 May 2017. Web. 8 September 2017.

- Powell, Alvin. “No Easy Answer for Health Void in Syria.” Harvard Gazette, 10 January 2017. Web. 8 September 2017.

- “Syrian Arab Republic Donor Update Q2 2017.” World Health Organization, August 2017. Web. 11 September 2017.

- Bakri, Ahmed Haj. “Rebuilding Latakia’s Healthcare System.” SyriaStories.net, 20 July 2017. Web. 11 September 2017.

- Arabi, Mohammad and Abdul Ghani Sankli-Tarbichi. “The Metrics of Syrian Physician Brain Drain to the US.” US National Library of Medicine: National Institute of Health, n.d. Web. 11 September 2017.

- Kaylin, Jennifer. “In the Midst of War, Future Syrian Doctors Trained with Help from Yale Faculty, Students.” Yale School of Public Health, 20 October 2016. Web. 2 October 2017.

- AFP. “Israel’s Defense Minister Says Syria’s Assad has Won the Civil War.” The Times of Israel, 3 October 2017. Web. 6 October 2017.